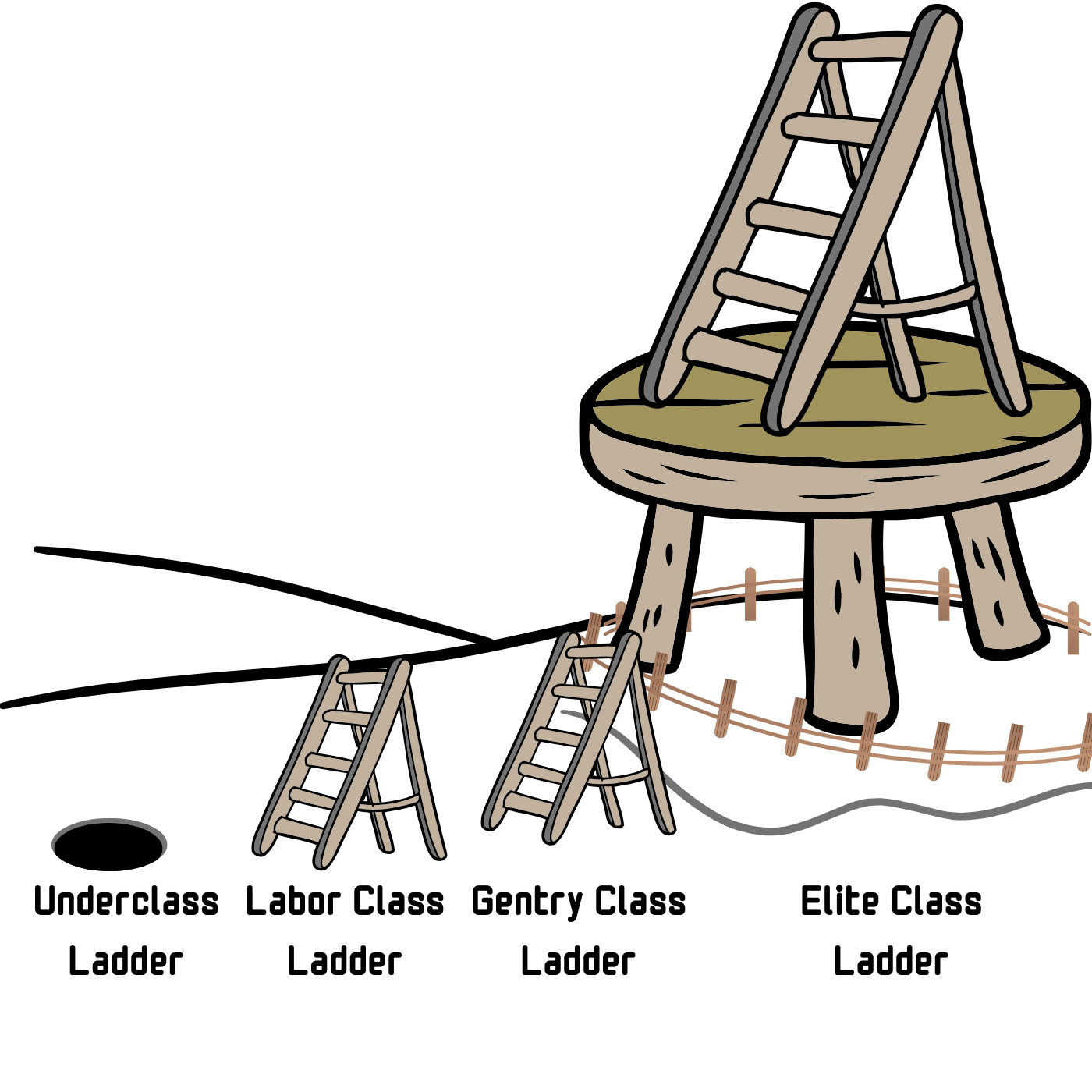

Three Class Ladders

(Adapted from Michael Church’s “Three Class Ladder” theory as outlined in this 2013 article on Daily Kos)

Social class refers to groups of people sharing similar socioeconomic conditions—such as livelihood, income, education, and social status—that shape their access to resources and opportunities, influencing both lifestyle and social roles. Within a capitalist society, class structure is fundamentally organized around one's relationship to production: whether they sell their labor for wages (Labor), engage in intellectual, institutional, or creative work (Gentry), own and control capital and private property (Elite), or are excluded from formal production and instead rely on informal, alternative, or criminalized means of survival (Underclass). These ladders reflect how capitalism stratifies people based on their economic function and proximity to power. It’s crucial to recognize that class or caste formations differ under other material and social systems. In feudal societies, socialist economies, tribal communities, or caste-based hierarchies, social stratification arises from distinct historical, spiritual, and cultural dynamics. The ladders described here are specific to capitalism’s structural logic, defined by private property, market competition, profit accumulation, and wage labor, and needs to be understood as such rather than mistaken for universal or natural categories.

The Underclass (10%)

The underclass includes the generationally poor. Many have never had traditional jobs, are third-generation jobless, and are not connected to the infrastructures of the other three ladders. This social class is also referred to as the lumpenproletariat.

People involved with

Legal System

Houselessness/Transient

Underground Sex Work

Undocumented Living Situations

Informal Vending

Others Marginalized or Excluded Groups

The Labor ladder (65%)

The labor ladder prioritizes work where status is based on income and effort.

Secondary Labor (30%)

Primary Labor (20%)

High-skill Labor (14%)

Labor Leadership (1%)

The Gentry ladder (23.5%)

The gentry ladder prioritizes access to reputable institutions and cultural movements and values education and cultural influence over income.

Transitional Gentry (5%)

Primary Gentry (16%)

High Gentry (2.45%)

Cultural Influencers (0.05%)

The Elite ladder (1.5%)

The elite class owns the majority of private property and values establishment control. To maintain dominance, they often exploit the labor and gentry classes.

The Strivers (0.5%)

Elite Servants (0.8%)

National Elite (0.19%)

Global Elite (~60,000 people worldwide)

The Elite Class ladder

The elite class (1.5%) owns the vast majority of private property and capital and aligns itself with preserving establishment or status quo power. To maintain its dominance, this class relies on economic extraction, cultural influence, and systemic control — exploiting both laborers and the aspirational middle strata. Within the elite class ladder, several rungs exist: Strivers (top 0.5%) are high earners who have gained wealth through entrepreneurship or investment but remain peripheral too deep institutional power. Elite Servants (top 0.8%) are top-tier professionals, executives, consultants, attorneys, entertainers, producers, who uphold elite systems without owning them. The National Elite (top 0.19%) includes legacy wealth holders, media barons, and corporate families who shape policy and public life within nation-states. At the highest rung (the actual bad guys) is the Global Elite, an estimated 60,000 individuals who operate across borders, controlling multinational corporations, financial institutions, and global forums. They are the ruling class of global capitalism.

The Gentry Class Ladder

The gentry class (23.5%) is a culturally and professionally influential ladder whose social position is shaped by education, institutional ties, and symbolic prestige, encompassing professionals in science, technology, healthcare, education, the humanities, the arts, and media—those whose labor centers on knowledge creation, cultural interpretation, public service, and technocratic management. The Transitional Gentry (5%) includes early-career researchers, resident physicians, arts workers, junior developers, adjunct faculty, nonprofit staff, and other highly educated but economically precarious individuals. The Primary Gentry (16%) comprises mid-career scientists, educators, clinicians, artists, unionized media professionals, and public service workers embedded in established institutions and generally committed to professional ethics and meritocratic ideals. The High Gentry (2.45%) includes tenured academics, senior healthcare administrators, renowned artists, and lead scientists whose voices shape cultural, scientific, and policy discourse. Cultural Influencers (0.05%) operate globally as public intellectuals, prominent creators, and thought leaders.

The Labor Class Ladder

The labor class (65%) sell their time, energy, and skills for wages. Their social position is defined by labor and employment, not by ownership or influence. Secondary Labor (30%) includes the most precarious workers: service employees, gig workers, domestic laborers, and many working-class artists. These roles are sometimes referred to as essential workers. Primary Labor (20%) includes semi-skilled workers, sanitation staff, hospital aides, administrative workers, local musicians and public transit operators, whose labor is more stable but still under-compensated. High-Skill Labor (14%) requires technical training: electricians, medical techs, stagehands, tradespeople, session musicians and support technicians. They may earn more but remain dependent on wages and vulnerable to systemic shifts. Labor Leadership (1%) includes forepersons, union stewards, and veteran workers who hold some influence within their sectors but still work under the constraints of corporate authority. Across all rungs, laborers share a common reality: they do not own or control what they produce, nor the systems that benefit from their effort.

The Underclass

The underclass (10%) is a group shaped by systemic abandonment, generational poverty, and institutional abuse. Described as the lumpenproletariat in Marxist theory, this social class includes those who are excluded from access to stable housing, employment, healthcare, legal protections, and education. Many have experienced or are currently experiencing incarceration, displacement, state surveillance, or targeted structural violence, including environmental racism, over-policing, and austerity economic policies. Some engage in informal or criminalized economies, including sex work, street vending, unlicensed caregiving, and underground labor markets. Others are undocumented immigrants, refugees, or stateless people who live under the radar. The underclass often builds resilient mutual aid networks, underground economies, and alternative forms of solidarity and community.

This framework highlights power dynamics: who owns, who serves, who labors, and who is excluded. These divisions aren't natural—they’re the result of systems built by humans and that system can be changed by redistributing resources and reclaiming our shared humanity.

We need to build genuine connections across class lines. Imagine if:

The Underclass ladder led community-based efforts around mutual aid.

The Labor Class ladder organized across trades for better conditions.

The Gentry Class ladder focused all efforts on raising class consciousness.

These shifts would counter the narratives the Elite use for division, like scapegoating immigrants, transgender people, teachers, or low-wage workers. The Elite stay in power by keeping us fragmented and distracted. But when artists, educators, workers, and the excluded unite in solidarity, that control becomes harder to maintain.

Cross-class coalitions have historically challenged unjust systems. Now is the time to build with a shared understanding of how capitalism divides us, and how collective action drives real change.

Foundational Labor & Class Struggles

Haymarket Affair (1886)

Workers from diverse ethnic and class backgrounds rallied in Chicago to demand an eight-hour workday. The protest turned deadly after a bomb exploded and police opened fire. It became a defining moment for international labor movements and May Day.

Battle of Blair Mountain (1921)

Over 10,000 coal miners—Black, white, and immigrant—took up arms in West Virginia to fight for union rights against company thugs and federal troops. It remains the largest labor uprising in U.S. history.

1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike

Maritime workers coordinated port shutdowns along the Pacific Coast. A citywide general strike erupted in San Francisco, making it one of the most successful militant labor actions in U.S. history.

Battle of Union Square (1930)

During the Great Depression, unemployed workers and communists protested mass joblessness and poverty in NYC. It was a major clash between the working class and the police, exposing state repression of labor activism.

Civil Rights–Labor Crossovers

Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike (1968)

Black sanitation workers struck for dignity, better pay, and safer conditions. Joined by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., their strike fused civil rights with labor rights under the banner “I Am a Man.”

Rainbow Coalition (1969)

Led by Fred Hampton and the Black Panther Party, this multiracial, cross-class alliance united Black, Latino, and poor white groups to fight racial capitalism, gentrification, police violence, and food insecurity.

Creative and Cultural Worker Strikes

Writers Guild of America Strike (2007–2008)

Writers halted Hollywood for 100 days, demanding compensation for streaming and digital media. It reshaped entertainment contracts and showed the power of intellectual labor.

Writers Guild & SAG-AFTRA Strikes (2023)

Hollywood writers and actors launched a joint strike to protect their labor from AI exploitation, wage theft, and streaming-era devaluation. With strong public support, these strikes marked a new wave of artistic labor solidarity.

Stardust Diner Unionization & Strike (2016–2018)

Performers at NYC’s Ellen’s Stardust Diner, known for singing while serving, organized under Stardust Family United. Despite threats, firings, and union-busting, they fought for healthcare, wage transparency, and safe working conditions—linking performance art to labor justice.

Education & Public Sector Movements

Red for Ed Teacher Strikes (2018–present)

From West Virginia to Arizona, underpaid teachers walked out for better wages, classroom funding, and dignity. These strikes mobilized communities and reignited the role of teachers as working-class leaders.

Graduate Worker Strikes (2020–present)

Grad students and adjunct faculty at universities like Columbia, NYU, Temple, and the UC system launched powerful strikes over low pay, healthcare, and academic precarity—bridging gentry-labor divisions.

Service, Retail, and Logistics Organizing

Fight for $15 (2012–present)

Fast food, healthcare, and service workers led strikes across the country demanding a living wage and union rights, sparking international solidarity campaigns.

Luigi Mangione Resignation (2021)

Mangione’s viral resignation letter from Balthazar exposed fine-dining exploitation and inspired service workers nationwide. His protest, framed as a “dignity strike,” illuminated class tension within food culture. (No Wikipedia article available as of now.)

Amazon Labor Union Victory (2022)

Led by Chris Smalls and JFK8 workers, this was the first successful union drive at Amazon. It defied traditional union models and exposed how frontline Black and brown workers are leading labor’s resurgence.

Starbucks Workers United (2021–present)

In cities nationwide, baristas defied corporate union-busting to demand better pay, scheduling, and healthcare. Their campaign helped revive the image of the unionized service worker.

UPS Teamsters Contract Win (2023)

With a credible strike threat, Teamsters at UPS secured major wins: pay increases, air conditioning in trucks, and full-time conversions. It was one of the largest private-sector labor victories in decades.

Rail Workers’ Sick Leave Battle (2022)

Rail workers nearly launched a national strike over denial of sick leave and brutal schedules. Though federally blocked, their organizing sparked national class awareness and solidarity across sectors.

Solidarity Forever!